|

|

REHABILITATING EMPATHY AS A TECHNOLOGY OF THE OTHERSARA MAGNO2023-07-27

Zooming out

We are living in a time that demands us to reconsider how we relate to each other. Colonial legacies and projects promoting globalization remain the dominant discourses which compel us to commit and connect to each other while, at the same time, we are witnessing reinforcements of national borders, which reduce our chances to engage and empathize with others. The distant other exists mostly through ambiguous, filtered and mediated images to which we tend to fail to empathize with. In Regarding the Pain of Others, Susan Sontag writes, “Our failure is one of imagination, of empathy: we have failed to hold this reality in mind” (Sontag 2003, 8). Given the conventional role of photography as a discipline which can produce documentation of reality, one would have thought that it would promote emotional identification with others. Instead, Sontag argues, its commodification has led not only to what has been considered as the resourceful exploitation of images by bourgeois society but also to a resistance of empathy in media discourse and practice. Acts of Empathy is the title of the Bienal'23 Porto Photography, an ambitious series of exhibitions that proposes to problematise the lack of empathy in our contemporary culture and society and revert this situation. If photography’s epistemological shock has told us that we have to be suspicious of images, it has also grown so deeply into the fabric of our society that we all know that we cannot live without them. How to reconcile photography and its expanded language of moving image, animation, HD vision and interactivity, with our capacity to empathize with others - this is, I believe, the greatest challenge posed to us by this iteration of the Bienal Fotografia do Porto. To embrace this challenge, we need to recognise that photography in its broadest sense, is not, and cannot be understood in a reductive sense, as simply documentation of reality. We, instead, are invited to re-engage with Walter Benjamin’s "art in the age of mechanical reproduction" (1935), a provocative text where the author positioned photography as the artistic medium par excellence that characterizes our contemporary society; as a medium that has radically altered our relationship to the world, including the means of knowing it. Contemporary photography, particularly in its expanded form is not static, rather it is an image in movement, circulating through various channels, participating in what Jacques Rancière (2004) has termed the “distribution of the senses,” short-circuiting our perception of the past and the future, and of cultures in the Global North and the Global South. Photography developed within the lexicon of conventional and recent technologies presented in the context of this Bienal is also positioned in dialogue with Ariella Azoulay's The Civil Contract of Photography (2012), in which photography is not limited to the photographic object but also includes the triangular relationship between photographer, subject, and spectator. In Azoulay’s own words, “The Civil Contract of Photography is an attempt to anchor spectatorship in civic duty toward the photographed persons who haven’t stopped being “there,” toward dispossessed citizens who, in turn, enable the rethinking of the concept and practice of citizenship” (Azoulay 2012, 17). Throughout the diverse range of exhibitions that constitute this Bienal, we are constantly asked to thoroughly reevaluate our understanding of photography's ethical status, our civic responsibility, and our role as spectators. Photography, we learn, is inseparable from the many catastrophes of recent history, and it generates a particular set of relations between individuals and the powers that govern them. The “civil contract” of this Bienal, subsequently, is one that promotes social change by mending our ability to empathize not only with others but rather with the main global issues that signal an urgent need for a collective change.

Zooming in

The first iteration of the Bienal Fotografia do Porto, “Adaptation and Transition” (2019), began by posing the question: “How can we transition towards a better adapted and more sustainable society, and how can thinking and artistic practice creatively expand discourse to translate into action?” Since then, this Bienal, produced by Ci.CLO, an organization based in Porto, has followed this premise to combine artistic practice and social change. The Bienal program interlinks parallel projects or platforms for artistic production such as, Vivificar, Sustentar, Conectar and Expandir (ViViFiCAR, To sustain, To connect and Expand). These action words describe the activities taking place within the period between the public presentation of the Bienal Fotografia do Porto in collaboration with different, regional municipalities in Portugal. Each of these projects has an exhibition program of its own in collaboration with public spaces and the local community. This year was the third iteration of the Bienal presenting evidence of six years of joining national and international artists to work with local communities on the basis of sharing knowledge and promoting care and creativity. But, above all, working towards rehabilitating empathy.

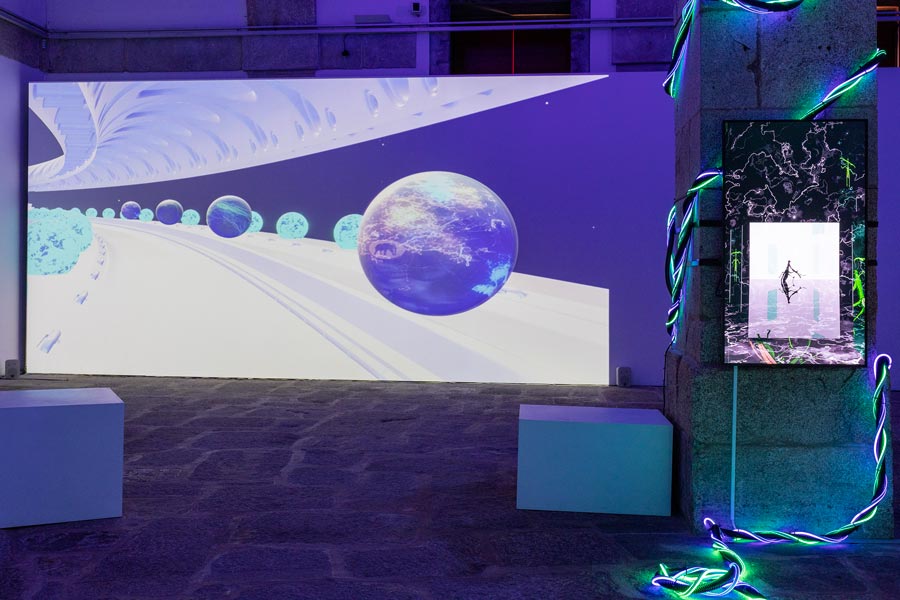

The Backpack of Wings, Hyeseon Jeong e Seonming Yuk. Bienal'23 Fotografia do Porto, 'Speculative Ecologies', Portuguese Centre of Photography, curated by Jayne Dyer and Virgílio Ferreira.

The Bienal’s curatorial emphasis Acts of Empathy challenges our “ethics of care” (Slote 2007), our means of representation of the other and the failure but also the possibility of rehabilitation of our own capacity to empathize with images of otherness. This is the case with the exhibition we find located in Centro Português de Fotografia, Speculative Ecologies, curated by Virgilio Ferreira and Jayne Dyer, the co.artistic directors of the Bienal. Divided between four large rooms we find photography and video-installation works by the artists Eliana Otta, Hyeseon Jeong, Seongmin Yuk, and Ursula Biemann. Each artist presents us with different aesthetic choices, yet all provide refined, attuned and playful representations of consequences of extractive economies, humans’ relationship to technology, and divergent ways of relating to property and ecology. The relation between photography and empathy, we learn through these artists' work, is a complicated one. Their speculative scenarios illustrate the ambiguity of whether images depicting catastrophes - such as the massacres of indigenous communities due to extractive economies - evoke empathy or compassion. These are two very different emotional states that we are asked to consider. For Hannah Arendt (1990), for instance, compassion is the silent demonstration of co-suffering: “compassion speaks only to the extent that it has to reply directly to the sheer expressionist sound and gestures through which suffering becomes audible and visible in the world,” which Arendt boldly believes to be undesirable in political discourse. Empathy, on the other hand, may be defined as the ability to identify with or understand the perspective, experiences, or motivations of another individual as well as to comprehend and share another individual’s emotional state. Empathy, therefore, implies a double movement: the projection of the self and the comprehension of the other. This is indeed more useful for social-political action and change, for it is not limited to connecting with the other in their suffering but rather compels the other to speak and overcome their suffering. Acts of empathy, rather than compassion, is what we see strongly represented in Ursula Biemann's films where she carefully balance didactics and poetics, as well as in Hyeseon Jeong and Seongmin Yuk’s pop aesthetics and political activism articulated through animation and moving image, which contrasts but also complements with Eliana Otta’s documentary approach involving photography and interactive video. Empathy for these artists means “staying with the trouble,” in Donna Haraway's understanding. As she put’s it: “We—all of us on Terra—live in disturbing times, mixed-up times, troubling and turbid times. The task is to become capable, with each other in all of our bumptious kinds, of response” (Harraway 2016, 1). Artists who are deeply involved with another person, who feels compassion for the other, may find it difficult to separate their own needs and desires from those of the other person, which may lead them to fail to empathize with what the other person needs or wants, and interfere with political decisions. The mechanism of empathy we see implemented here, however, seems to aim at something else: a state of emancipation or autonomy of the represented subject, or even the viewer.

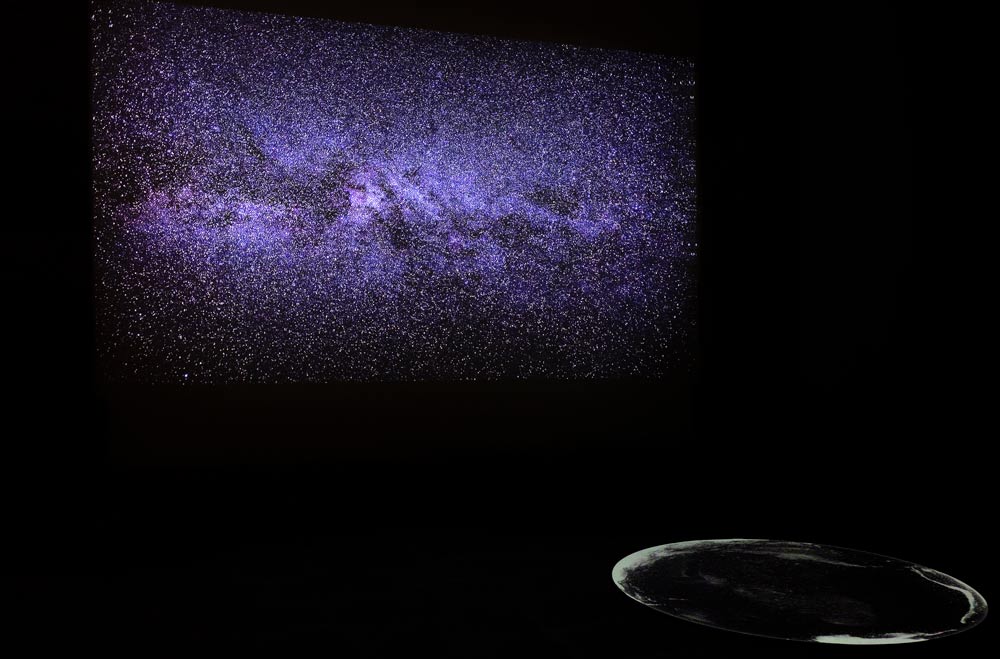

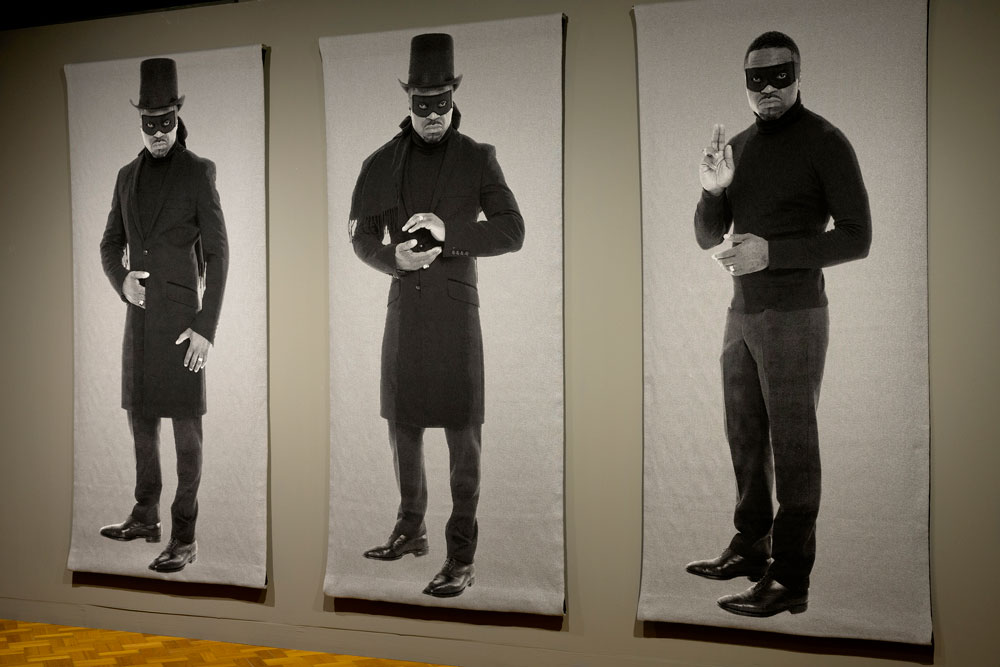

The knight of the long knives I, Athi-Patra Ruga.

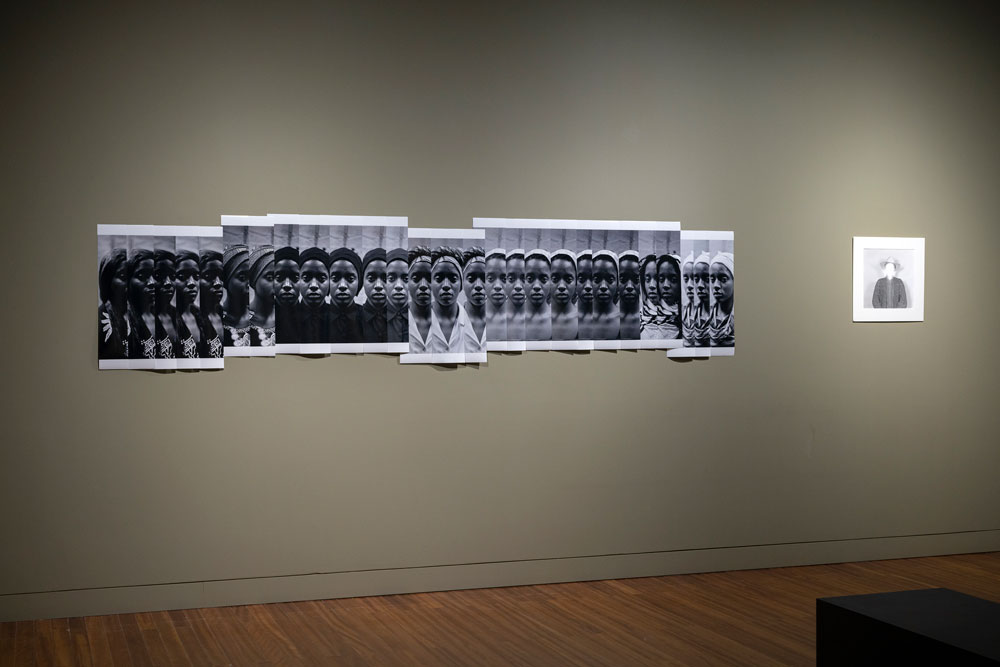

The exhibition Deep Blue curated by Mónica de Miranda, also illustrates how empathy could lead to a sense of emancipation or autonomy for its subjects. It brings together the artists Athi-Patra Ruga, Buhlebezwe Siwani, Faisal Abdu’Allah, Helena Uambembe, Kudzanai Chiurai, Mónica de Miranda, Sandim Mendes, Sethembile Msezane, Silvia Rosi, Xaviera Simmons and Zineb Sedira, whose work is distributed through several rooms of the Museu do Porto - Palacete dos Viscondes de Balsemão. Here we find large prints documenting performative acts that can be identified with what Kodwo Eshun describes in More Brilliant than the Sun (1998) as Black Accelerationism: a wilful attempt to clear away certain habits of thought and feeling in order to imagine a future that is seeking to realize itself in the present. This group of artists push socio-political boundaries to create a space for autonomy and emancipation of the individual, an idea that can be seen in their works and the exhibition as a whole.

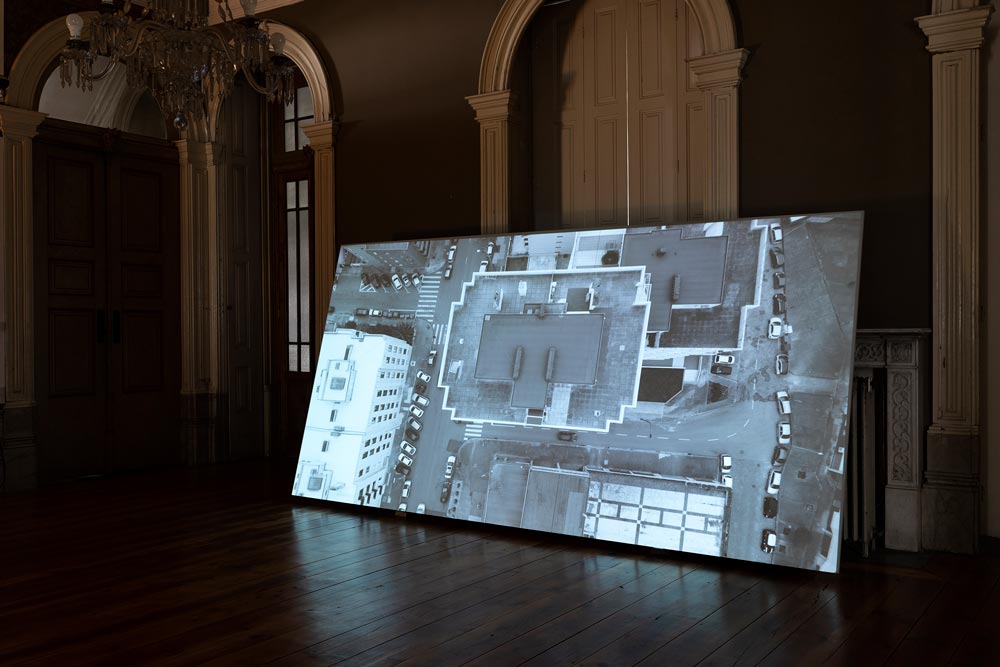

O Carpinteiro, Helena Uambembe, 2018.

“Empathy does not leave the subject where it first met her. If it works (as a technology of the other), then it draws the subject elsewhere and into a different state” (Lobb 2015, 232). To leave the subject in a different state is also what marks the difference between empathy and compassion – (Lobb 2015, 232). Another strong example within the Bienal is the exhibition In Light or Shadow of What Was and Still Is - an initiative of Spain’s Casa Arabe that brings together perspectives of contemporary Lebanon, precisely thirty years after the civil war that ravaged the country. The complexity of the subjects represented by each photographer in this exhibition located in Casa Comun - Reitoria da Universidade do Porto, ask us to consider that what is necessary is not just a partial identification with the other but also an understanding of the other’s differences. The photographs, here carefully selected, promote a kind of a will to empower, in the sense Lobb refers to, for they were shot by the artists who have been subject to Lebanon’s most recent catastrophe: what has become known as the 2020 Beirut explosion. At its limit, the will to empower has the intention to prepare the other for the moment when the person who empathizes will cease their authority and the process when the other becomes an authority itself begins. Contrary to the will to power, which is a technology for the domination of the other by making the other do what I want him to do and thus having a determined end to that will, the will to empower can only be the opposite of that: it will always lead to uncertain ends.

Zooming out

Here is the paradox of autonomy: if empathy helps to provide the conditions for autonomy for the ‘other’, the empathizer cannot expect the autonomous other to behave or to conduct herself, in a particular way. If empathy happens as a ‘technology of the other’, in line with this exhibition’s intention, “it would short-circuit the other’s emergence into the subject who can verbally articulate protest and signal the nature of their own needs” (Lobb 2015, 230). Here, we might envision a possible conclusion: Acts of Empathy have the potential to activate forms of reflexiveness and progressive awareness that might lead to critical autonomy and an empowering effect on the viewer, but in the end it is utterly impossible to measure the extent of its impact in the world. What makes acts of empathy possible? Perhaps we could say that it is about the common task of understanding the world. While only a few artists have been mentioned here to sum up the main issues, in fact, this Bienal puts forward a very ambitious task: it gathers the work of seventy artists and fourteen curators from twenty-seven countries. This aspiring project deserves attention and respect (for it is an important step in problematising empathy). However, ultimately, one cannot but notice that it is perhaps best understood indirectly by using the parable of a blind group encountering an elephant. Each of the group touches, senses, and recognizes a part of the elephant, declaring it similar to what they touch: the trunk, tusk, or tail. People who can see the elephant will not know better than those who cannot. This is because, while they might see its gray skin color, they may not be familiar with its texture or smell. In the end, none of the group can truly claim to know the totality of the elephant, they are only able to verify particular elements which they know, feel and recognise. It may not even be possible to combine these partial accounts into a complete picture of the elephant as a whole - or as a world. The way each of us comes to know things shapes, in part, the things we know and empathize with. The project of making the world knowable is paradoxical in this sense: nothing indicates that its components constitute the whole. As such, this Bienal focuses on a few spheres of knowledge, of empathy building, rather than claiming to comprehend the whole world at once. Artistic production, and the photographic techniques involved, enables us in order to make part of the world knowable. What we can take away from this biennial is that the state of things today, in what we have come to term as the Anthropocene, is particularly troubling. Each individual exhibition within the Bienal touches on small elements of a wider problem but works collaboratively, as a common task, to put the parts together. Not so much to produce a seamless picture of the whole as to understand the differences between all the partial sensings of the world. The common task is to, through acts of empathy, produce knowledge of the world and an understanding of our place in it. Here, the notion of empathy can be thought of as a bridge, connecting us to the world and inviting us to make real changes, crossing from our current indifference to a newfound sense of civic responsibility.

Sara Magno

Arendt, H. (1990) On Revolution. Penguin Books: London

|

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)