|

|

ALFREDO JAARLA FIN DU MONDEGALERIE LA PATINOIRE ROYALE BACH Rue Veydt 15 1060 Bruxelles 04 SET - 14 FEV 2026 The last memory

COBRE PAMPA — Andrés Sabella

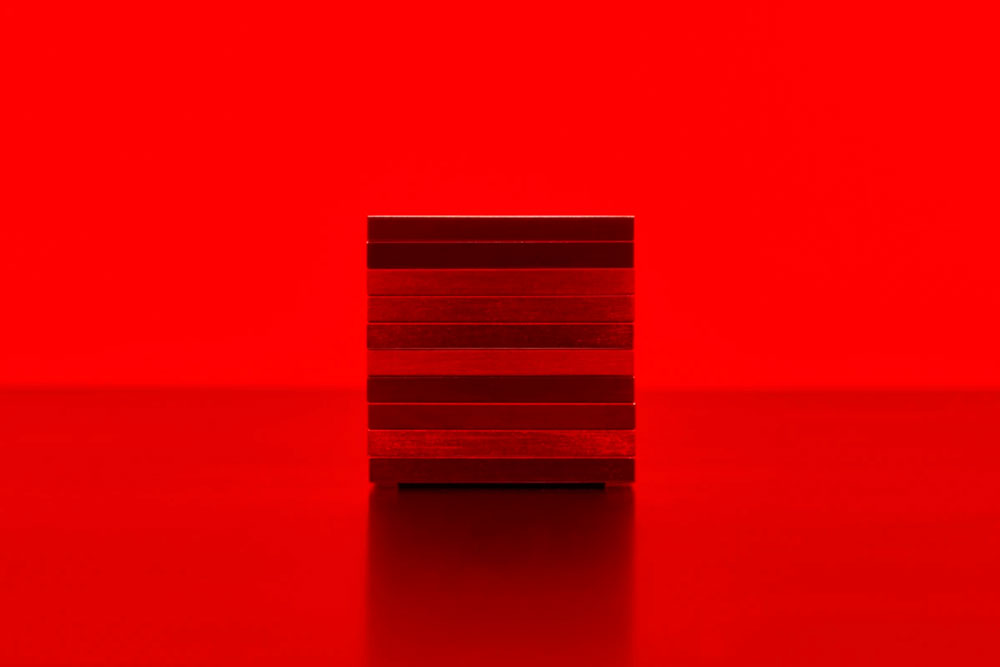

An underground theater — that is the first impression upon passing through the dark curtain that leads into La Fin du Monde, Alfredo Jaar’s exhibition at Galerie La Patinoire Royale Bach in Brussels. The entrance marks a shift into a space where perception is quietly rearranged. Bathed in low-intensity, highly saturated red light, the room feels at once cavernous and theatrical, so that the viewer’s first steps into the gallery evoke an isolated chamber that could easily lie deep beneath the earth’s surface. This impression is reinforced by the exhibition’s first element: a text in large letters spanning two walls. It presents technical information on the ten minerals most used by global industry — and on the geopolitical consequences of their extraction: copper, tin, nickel, cobalt, lithium, manganese, coltan, germanium, platinum, and rare earths. Between the walls, black curtains with a central slit invite us to enter what resembles a stage embedded in the Earth’s rocky core, where we ourselves become the actors: the last humans, implacable witnesses and agents of the end of times, forced to endure our own fastidious presence in the nearly empty epilogue of a world already gone. This dystopian setting holds the exhibition’s single artwork: a tiny cube measuring sixty-four cubic centimeters. The striking object inspires a peculiar fascination with its perfectly polished, stratified surfaces, resembling the Earth’s lithosphere. It is composed of the materials most consumed by capital’s extractive machinery — an engine fueled by material and epistemic violence, whose byproducts are the humanitarian and environmental crises scattered across the planet. This small yet compelling piece evokes a sense of the sublime: an extraterrestrial block of concrete, perhaps, or a curious three-dimensional pixel, evoking both its unusual appearance and the traces of human labor alienated from the countless everyday objects that surround us, from solar-paneled buildings to computers. The substances that compose them are alienated as well — minerals sourced from reserves as varied as the human body and the Moon. Made of the same elements, people, objects, and planetary satellites exist in continuity; the time of celestial bodies is also the time of living beings on Earth. The artwork’s singularity is amplified by Jaar’s display strategy: within the vast, thousand-square-meter hall, that small inorganic structure becomes a disproportionate gravitational center, drawing toward it the political charge of matter itself.

The object represents the smallest possible unit of what Isabelle Stengers describes as cosmopolitics [1]. Functioning like a tiny time capsule, the metal cube longs to transmit something of the present to a hypothetical viewer of the future. Anthropologist Elizabeth Povinelli has suggested that biological life is merely one internal organ of a planet that will persist long after our extinction [2]. Without denying the agency of inorganic matter, La Fin du Monde asserts responsibility for this brief interval within cosmological time to which we belong, reminding us that even the so-called “green economy” inflicts violence upon the world and its living beings. Copper and lithium, for instance, are considered strategic raw materials for the energy transition, vital to the production of electric vehicles and energy-storage systems. Yet beyond powering cars and batteries, these metals also infiltrate the bodies exposed to their extraction. Researcher Marina Weinberg has coined the term “bodies of copper” to describe the effects of copper mining in Chuquicamata on local communities [3] — one of the world’s largest copper mines, located in northern Chile and explored since the nineteenth century. The Atacama Desert also contains one of the planet’s major lithium reserves — the Salar de Atacama — where irresponsible extraction has caused severe socio-environmental harm to local populations such as the Licanantay. This governance of bodies — another term used by Weinberg — is regulated by private companies whose histories are deeply entwined with the political history of Chile itself: SQM (formerly Soquimich), responsible for lithium extraction, emerged from the wave of privatizations instituted during Augusto Pinochet’s dictatorship — a process that notably benefited his then–son-in-law, now one of the company’s major shareholders. Inscribed in the landscape, the historical and political ties between Chile’s dictatorship — the same regime that led Jaar to leave his native country — and geology extend even further: in the desert sands, the Chacabuco concentration camp operated between 1973 and 1975. Its thirty-six hectares had once been used for saltpeter extraction. Entirely isolated in a harsh, inhospitable territory, the military government needed only to add a few additional mechanisms of control to repurpose the extractive site. On the soil of that dramatic geography, native minerals and human bones intermingle — remnants of killings carried out at the beginning of the dictatorship and preserved by the region’s extreme dryness: a history irreparably amalgamated with the arid material of the desert, pointing toward a politics of matter and substances. It is this politics that Jaar’s exhibition invokes. His geopoetic strategy — a term used by geologist Adam Bobbette [4], who contributed to the research for La Fin du Monde — seeks to reveal the historical and political inscriptions etched into the Earth’s crust. To achieve this, the solid layer of the world is overturned, exposing its underside as the viewer is positioned within it. As the work excavates the temporal strata of substances in all directions, what emerges is an archaeology of the future; from this archaeological gesture, only one final memory remains, destined for the end of the world — the ultimate synthesis of the mineral drama corroding our present. Antônio Bispo dos Santos names cosmophobia as the disconnection between humans and the physical world: the product of a colonial project bound in a perverse alliance with capital. The activist and writer also recalls an anecdote from his childhood in Quilombo Saco-Curtume, in northeastern Brazil:

“Where is the end of the world?” The wise man placed his heel on the ground, curled his toes, turned his foot into a compass, drew a circle, and said: “The end of the world is here, where my heel was, because the world is round.” And the king asked: “And the beginning of the world?” “It is here as well,” he replied. Here is the end and here is the beginning — it depends on where one stands. [5]

A memory lodged at the center of the Earth. With a density that defies the scale of the small cube it occupies, it seems ready to pull everything toward itself, like the premonition of a black hole. Yet in this near-collapse, the memory still resists — suspended between the end and the beginning of the world.

Isabel Stein

:::

Footnotes [1] Cosmopolitics (2010)

|